This isn’t entirely new but a paper I have given a few times now, slightly tweaked as it isn’t being given orally. But it belongs here, I think, as the process of writing this was a bit of revelation. When I last gave this paper, a historian who I massively admire told me that I needed to carry on the ‘free association’ of the final section because it had made him gasp (!) but admitted that he didn’t know how. I don’t know how either.

In the final years of her life, when my Grandma was moved into a care home, she decided that she was staying at a Blackpool hotel. ‘It’s great here,’ she told my aunt, lowering her voice to a whisper, ‘and everything is free’. One of the oddly touching activities that the staff put on for residents was a weekly night at ‘the pictures’, where these men and women who had largely grown up during ‘the age of the dream palace’ were sat in rows, with the film turned off for an interval half way through while ice-cream was served. One of the films was Grandma’s favourite, South Pacific, which she had reportedly went to see at the cinema at least ten times on its release in 1958, by which time she was not young, but a married woman of 35, who had already had two children and had lost another. Fittingly, one of the famous songs of this Rogers and Hammerstein musical urged to ‘keep talkin happy talk, talk about the things you’d like to do/If you don’t have a dream/You gotta have a dream/Then how you gonna have a dream come true?’

Grandma was the grandparent I knew the longest but also the least. My father’s relationship with his mother was complicated (though saying this out loud, I wonder: whose isn’t?) Dad had his reasons, which I respect and won’t interrogate now, even though I think – from the privileged position of not having had a childhood marked by poverty and other social injuries – that he judged her harshly. Grandma’s main topics of conversation, second only to her knees, were bingo and bus rides, which was largely how she spent her days by the time I knew her. Conversation was rarely deep except on the odd occasion when she would burst out with profound anger, largely relating to Christopher – her baby who died in childbirth in the ‘50s, for which she firmly blamed the midwife – or the Conservative Party (‘Your Grandad was never without work when Labour was in!’). She talked little about her childhood, save the story that her father, a tram driver, used to throw sweets behind the tram for her to chase after while driving down Kingsway, the main arterial road through South Manchester, built in the late 1920s and down the route of which my family lived for the rest of the century.

In 1939, my Grandma’s father – my great-grandfather – took his own life. Due to the immense stigma surrounding suicide, the circumstances surrounding his death became a family secret that was hinted at occasionally but never elaborated on, until the mid-1990s when my father broke down while watching the famous final scene of Blackadder Goes Forth, when the main characters meet their fate as they go over the top on the Western Front before fading into a field of poppies. The story he told me was compelling, especially as I had recently been instructed to memorise Wilfred Owen’s ‘Dulce et Decorum Est’ in my English Literature class. Having served as a young man in the First World War, Robert Voss had returned a broken man and, on the eve of another global catastrophe which he might still be young enough to be conscripted in, decided he could no longer live with the risk. Around this time, my father had the only photograph of my great-grandfather that had survived in our branch of the family restored and enlarged: his image, a boy in uniform, literally rehabilitated and placed on the mantlepiece.

As time went on - and as I became a professional historian, I guess - something about this narrative nagged away at me: it was not that I disbelieved my father’s story but that it somehow seemed too neat. After years of telling myself that I was not interested in family history –that I was not that kind of historian – I suddenly found myself on a database searching for the documents of my great-grandfather’s life and death.

The bare “facts,” as I was able to ascertain from the public record in minutes after decades of furtive whispers, are these: Robert Voss was born in 1897 in a poor part of Manchester to Francis Voss, a grocer’s assistant and Sarah Voss, nee Haddock. He lost his mother at the age of 5. His father remarried a year later, only for his new wife, Alice Norton, to die after a year in 1904. In 1905, Francis married a third time, although this wife – Marina Alice Woodhall – managed to make it to 1920. Francis survived both all of his wives and his son Robert, dying in 1940.

Francis had himself been baptised in the notorious Manchester slum of Angel Meadow in 1873, after the marriage of Robert Voss and Mary Walsh in Liverpool in 1871. Neither party in the marriage was able to write their name. Francis’ father – a hawker – died in mysterious circumstances in Liverpool in 1886. An article in the Manchester Evening News tells a sad tale of a ‘Singular Death of a Tract Seller’, last seen in a bad state near the River Mersey and his body found upstream several months later.

So far, you are probably getting the sense – I certainly did – that Robert Voss’ life wasn’t exactly a bed of roses. It might then, be understandable that he volunteered for the army early on. He entered the war in September 1915 and fought in the Dardanelles, initially as a private in the East Lancashire Regiment and then the Labour Corps, which was a move that was often the result of an injury. In the 1921 census, he and his wife Monica were boarders with Ernest and Isa Kirkham in Cheetham, Manchester. Ernest was a removal van driver, and Robert was, by then, already working as a labourer for Manchester Corporation Tramways while his wife performed ‘house duties’ for their landlords. Robert relatively quickly progressed to being a conductor and two children, Robert and Joan, arrived in 1922 and 1923. Things seemed to be on the up until, in around 1934 or 1935, he finally got to drive his own tram. Then nothing until the death recorded in the admissions of the Withington Workhouse and referred to the Coroner in March 1939. Verdict: suicide while the balance of mind was disturbed.

With the next click, came the most shocking– to me, anyway – document of all: a report of the inquest a few days later, again in the Manchester Evening News, headlined ‘TRAM DRIVER FEARED BUS CHANGE OVER’. The story continued: ‘When a Burnage man who had been working on tram cars for twenty years heard that buses were to be substituted for trams, he began to worry … ‘ My great-grandmother had testified that they ‘had been married 19 years and her husband had always worked for the Corporation Transport department. He was made a tramcar driver about four years ago. He did not like the idea of tramcars being replaced by buses and had become very depressed about it.’ There is no mention of the war.

This completely different framing of my great-grandfather’s death floored me. I did not know what to do with it. It now became my secret, as I could not bring myself to tell my own father what I had found. The image of a man in his early forties not eating for days as he read and re-read a book titled How to Learn to Drive a Motorcar was clearly tragic but didn’t feel like the right kind of tragedy. It wasn’t a baby-faced boy soldier fading into a field of poppies but the panic of man unsure of his ability to sustain the life he had created for himself and his family on his return. A little contextual research showed, however, that my great-grandfather was not the only one affected by the coming of the buses, as Rhodri Hayward’s study of the industrial dispute around a nervous condition named ‘busman’s stomach’, a distinctly modern complaint, in the late 1930s shows.

After my father’s death in 2020, and following my own severe mental illness that had involved period of suicidal thoughts and ideation, I felt myself being drawn back to these few column inches. This time, though, I knew from experience that there is never one reason for, one event that leads to, or one story to be told about suicide. It became clear to me that just because there was no mention of the war didn’t mean that my family had been lying; they had just done what the coroner had done, and what the Manchester Evening News reporter dispatched to court did, and told a story to try and render the unfathomable understandable, to make some kind of sense.

Zooming out from the story, though, takes us somewhere else entirely. Look at the whole page, and we are suddenly thrown into the complexity of interwar provincial life, of change at breakneck speed, into the noise and confusion of the ‘people of the aftermath’ to use Matt Houlbrook’s phrase. People like my great-grandfather who returned from the trenches to drive tramcars, as modern life marched past them. At first the surrounding headlines read like dada-ist poetry: ‘M.P. Joins Balloon Squad’; ‘Boy Raiders Say Woman Exclaimed: Blimey, You’ve Got Rubbish!’; ‘Gaoled Footballer Freed’, ‘Artist’s Model Godiva’; ‘Princess Has Banking Account’ (Princess Elizabeth that is: presumably it’s closed now); ‘Something is Out of Tune’ declares the ominous headline of a report of a brass-band strike.

Looking up from our story, we find that Robert Voss’ inquest was not the only one that involved fears around employment, or lack of it. His case is linked by a strapline to another: ‘Two Stories of Men Who Took Their Lives Because of Job Worries Were Told to the Manchester City Coroner To-Day. One Wanted to Earn More to Help His Family, the Other – a Tram-car Driver-Feared the Introduction of Buses.’ A shop-assistant of twenty years of age, the ‘sweetheart’ of this younger man testified that he was worried ‘because he was not earning enough money to help care for his five young brothers and sisters’. ‘“He was the best young man any girl could have,” she said, brokenly’.

Look to the left, and we are enticed by J. and J. Shaw’s Spring Furnishing Offer! Three complete rooms for only £48 pounds and ten shillings or on the deferred payment plan of £5 down and twenty-four payments of £1. The aspirational dream of Super Deep Pile Malabar Quality Carpets at accessible prices.

To the right, we are given the hard sell for Samona, ‘The Wonderful Medical Restorative’. There appears to be little that Samona cannot do. It ‘ensures longer life, general fitness and vitality, even in old age’. Orange tablets for men and brown tablets for women bring immediate benefit. Mancunian skeptics of such miracle cures might be directed to the Advertiser’s Announcement above, titled ‘Sore Feet’ and written especially for the company by the famous Lancashire dialect writer Tommy Thompson.

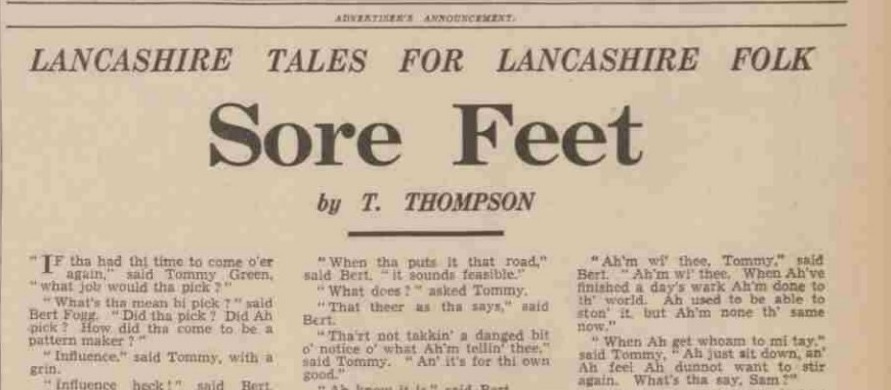

Subtitled ‘Lancashire Tales for Lancashire Folk’, a dialogue between working men Tommy and Bert gets philosophical at remarkable speed, as they contemplate the concept of reincarnation, before their friend Sam chips in to recommend a remedy for sore feet:

“Dosta believe in ancestors havin’ ony influence on our characters an’ sich?” asked Bert

… “Tha doesn’t want to bother thi yed wi’ that soart o’ muck,” said Tommy. “Ah leave mi ancestors alone, an’ Ah dunnot see why they should bother wi’ me.”

Despite the disclaimer that ‘all characters in this story are purely imagined’, I admit to having gasped out loud when I realized that these words were printed in line with the story of my own, very real, ancestor.

Why not leave mi ancestors alone? Why should they bother wi’ me?

I’m not trying to rescue them, least of all from the ‘condescension of posterity’. Grandma and her father were consistently condescended to in life and the need for their rescue has long since passed. But I do want – and feel compelled, as a historian – to acknowledge and explore the complexity of their lives and times. I find their legacies difficult, complicated, unsettling, contradictory and yet comforting. Historical narratives tend to compartmentalize and categorise: the soldier, the shellshock sufferer, the father throwing sweets out of the tram to his daughter are treated as different people; the effects of mass mechanical warfare abroad separated from the precarious war against poverty at home. Family history, however refuses to be contained. It is, as Alison Light puts it, ‘a trespasser, disregarding the boundaries between local and national, private and public … taking us by surprise into unknown worlds’.

Today, I have tried to conjure for you an unknown world of provincial inquest reporters, men taking orange pills and women taking brown ones, fictional workman discussing reincarnation in Lancashire dialect: a world where sweet-hearts might have once dreamt of deep pile Malibar carpets while princesses opened bank accounts. I cannot rescue or recover mi ancestors. But if they can help me tell the stories we live both by and with, I shall let them keep bothering mi.

Oh Cath, my heart is a little broken by this story. How tragic, the changes that leave people behind. This is such a vulnerable and beautiful retelling of your own story and your family's. Thank you for sharing it.

What is an inquest for? It tidies up a mess, and reduces the whole of a life into a couple of sentences. It isn't looking for complexity, quite the opposite. Far easier to blame a terror of the bus than look at old traumas, especially in a country barely recovered from one war, refusing to acknowledge the traumatic load, heading into another one.

People are complicated, and accommodating that in any kind of history is hard...but this, Cath, is beautiful.